Hi all,

Welcome to the 3rd edition of Signals & Stories!

If you’re just joining us, check out the first two editions below:

Why so many top-down decisions fail — “Policy resistance happens when our attempt to fix a problem—usually through some rigid, top-down mandate—actually makes the problem worse.”

What’s holding you back? A simple signal — “Our ability to grow is therefore proportional to our ability to continually anticipate and address new limiting factors.”

Have a Happy Mother’s Day and good start to the week.

—Brendan

📖 The Story

In an alternate universe, I quit my corporate job after making excessive PowerPoint decks and move to LA to become an actor. With $30,000 in savings and a part-time job at Peet’s Coffee, I figure I can survive at least a year without steady work. I move into a greasy flat in West Hollywood—the windows have those cracked vertical blinds—and lease a Toyota Camry and pretend I don’t care what people think as a coping mechanism for my now lowered financial status.

One twilight, I drive over to the In-N-Out on Sunset Blvd for dinner. Waiting in the drive-thru, feeling bored, I pull out my phone to read articles. I took statistics in college and see one that piques my interest… and anxiety. Of the ~32,000 actors (!) employed in the U.S., only the top 5%—just over 1,400 people—make more than $200,000 a year. The top 10, the Tom Cruises of the world, make more than $20 million a year. The distribution takes on a characteristic power law shape, with a long-tail out to the right.

What’s the probability I make a highly lucrative career as an actor? Frighteningly low!

I repress my existential crisis by convincing myself that I can be part of the precious 5% that will “make it”. I’ll out hustle and out network the other young, handsome narcissists funneling-in from across the world. “Here’s to the ones who dream” sings Emma Stone in La La Land, “foolish as they may seem.”

What I do not yet realize is that a nontrivial percentage of my odds of “making it” will be out of my control, driven by luck.

A simple model can explain why.

🧠 The Signal

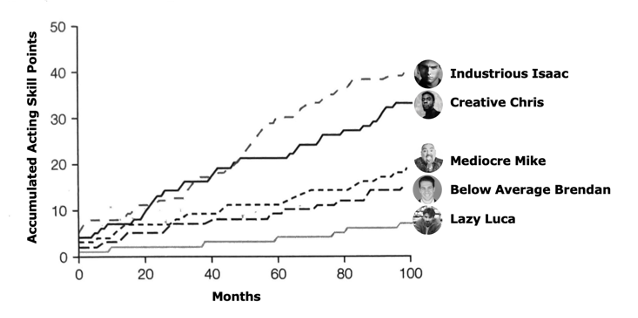

Five actors move to Hollywood in May 2024: Creative Chris, Mediocre Mike, Lazy Luca, Below Average Brendan, and Industrious Isaac.

As their names suggest, some of the actors are more skilled and ambitious than the others:

Let’s assume they each audition for the same part, and that the probability they each get the part is in direct proportion to his respective skill level. Industrious Isaac has a 33% chance (5 points divided by 15 total points) of getting the part, while Lazy Luca only has a 0.7% chance (1 point divided by 15 total points).

Let’s also assume that once an actor gets a part, he can add one skill point to his resume. If Isaac gets the first part, his new skill level is 6, and his odds of getting the next part would now be 6/16 or 37.5%. In month 2, there is another audition for the next part, and the process repeats. This simulation is called a preferential attachment model.

The model makes the simple, but reasonable, assumption that an actor with a larger reputation today is more likely to land a part tomorrow. This an important assumption. It means that when a director selects an actor, she factors-in the actor’s accumulated reputation and success (or in my case, lack of it). She doesn’t make the decision in a vacuum, relying purely on the audition and screen tests. Given movies are ultimately businesses, and more famous/accomplished actors draw bigger crowds, this is a reasonable assumption that we’ll see leads to a characteristic effect: the “rich get richer”.

So what happens when we run this simulation for several years into the future? Who accumulates the most points? Who “makes it” in Hollywood? Below are the results for a few different simulations that suggest an answer. These results are re-purposed from Michael Mauboussin’s book The Success Equation. (I just added the “creative” names.)

In simulation 1, Industrious Isaac, the favorite, gets an early advantage and keeps it throughout his career.

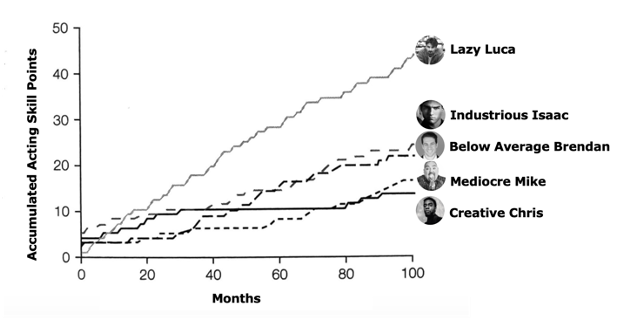

In simulation 2, Mediocre Mike languishes a bit initially but then gets a series of big breaks. Once he starts accumulating auditions, his chances of securing more also increase.

In simulation 3, Lazy Luca, the lethargic long-shot, gets lucky in his career. A few early breaks put him in the lead, and then he keeps up the momentum.

In short…

The actors all start relatively close in skill level but diverge widely over time. The gap between “rich” and “poor” and “success” and “failure” is huge.

Actors who start getting roles are more likely to get future roles; they develop a rich-get-richer reputational momentum. Sociologists also call this the Matthew Effect (from Gospel of Matthew: “For whoever hath, to him shall be given, and he shall have more abundance…”). Once one actor establishes a big lead, no one else can really catch up.

More skilled actors have the greatest probability of success initially, but it’s not guaranteed success! Sometimes,

co-workersactors with less skill take the initial lead a run with it. A single lucky break can have huge carry-over effects.The results therefore vary widely across scenarios. In one life Industrious Isaac sees his hard work pay off. In another, he watches Lazy Luca, who is perhaps a nepo baby, move ahead after a few lucky breaks.

I had moved to Hollywood assuming that hard work is rewarded with acting success. The truth is that in one “world” I may succeed beyond my wildest dreams if I get the right break. Or I could fail miserably. And there is not much in between.

So what does a simulation about actors teach us?

When there are few winners and many losers in a career, such as acting, there is often a contributing path dependent, “rich-get-richer” process at play. The person with a bigger reputation and more followers today is given… a bigger reputation and even more followers tomorrow. Path dependence also means that lucky breaks are mission critical because you get locked-in 🔒 to future opportunities.

This information can help us spot other careers that resemble acting, in which there is vast inequality between the highest and lowest earners. Let’s call these superstar careers. Influencers, authors, and tech entrepreneurs all experience superstar effects, in which there are a handful poppin’ bottles and then a vast horde barely getting by… If you aspire to a superstar career, be prepared for a different style of game vs. medicine or accounting in which there is more of a bell curve in earnings.

To succeed in superstar careers, both luck and what I may call “reputational momentum” matter. You can increase your luck by going to parties, meeting new people, and praying you meet someone who can change your life. Cue “Someone in the Crowd” from the La La Land soundtrack on my Spotify. As for reputational momentum: the main prescription is not to screw it up once you have it. “The first rule of compounding”, Charlie Munger said, “is to never interrupt it unnecessarily.”

If you must hire someone in a superstar career, you might be overpaying if you hire the biggest superstar. Because A-list superstars accumulate their extreme reputations and earnings due mostly to luck, there is likely a small skill difference between them and the B-list. CEOs are an example. Some research has shown that there is negligible difference in skill between the CEOs of the 10th largest and 300th largest corporations, though the former group may earn 10x that of the latter group. In Moneyball, the Oakland Athletics assembled a winning MLB team at a fraction of the cost of its competitors by finding undervalued players and eschewing the A-list superstars.

And even if you’re not an influencer, CEO, or actor, many of the above takeaways still apply to your career decisions too.

Our lives are shaped by luck—often more than we’re comfortable admitting. Everyone has a story about how they got their first job through a random classmate or after making small talk with the interviewer about some random mutual hobby. Actually, both of those happened to me.

Reputational momentum applies too, though it may just carry you to the next promotion instead of an Oscar. As Morgan Housel says:

“Reputations have momentum in both directions because people want to associate with winners and avoid losers. The more successful you are the more people want to be associated with you—which is great. But that’s equally powerful in reverse.”

In an alternate universe, I moved to Hollywood to become an actor. In this universe, I read about path dependence in college and, understanding the risks, went into consulting instead.

🎓 Further Reading

The Success Equation, Michael Mauboussin: Explores the balance between skill and luck in determining outcomes in various domains, from sports to business. Mauboussin argues that while skill plays a significant role in success, luck is often underestimated, and understanding the interplay between the two is crucial for making better decisions and achieving success.

Thanks for reading!

Signals & Stories is a newsletter that explores the recurring patterns we can recognize to make better decisions—in business and life.

If you like Signals & Stories, feel free to share with a friend or colleague.

—Brendan